MLK Installment #5

Lawrence Funderburke

Classism in Corporate and Entrepreneurial America: The Economic Mobility Road Is Paved by Rocky Experiences

We have more of a class crisis in this country than a color conflict. MLK fought for financial justice just as much as he did for social recognition, political capital, or even racial harmony. Without equity or economic skin in the game, black and brown Americans will always feel like second-class citizens, no matter how we’re genuinely (or insincerely) accepted in this country. Equality is the historical payout for an injustice debt that has accrued with interest and deferred through countless IOU empty payments for hundreds of years, but equity pays off an outstanding bill owed to legacy benefactors by vested parties for generations to come. That includes you, me, us. If the government is limited in what it can do to create a more fair and just economy, without any guarantees of course, then who should pick up the slack? I nominate corporate America and entrepreneurs to step forward, the two formidable drivers of economic ingenuity.

In this final installment of the MLK Series on Race in America, you’ll be challenged on three fronts. First, you will be asked to step out of your comfort zone to better understand colleagues who are stuck, or perhaps stranded, inside their place of refuge. Second, you will be confronted with (or by?) information that may very well contradict generally accepted attitudes and beliefs about social classes, including your own. Third, you will be given a mandate to broach the subject of classism with others inside and outside the workplace to make an uncomfortable subject comfortably rewarding to scrutinize. If you’ve read my other articles, I’ve been consistent with this theme: intentional growth can only be achieved through experiential discomfort. Take a deep breath; we’re going up to a high place to meet others in their low space. (Yes, oxymorons are an integral part of my unorthodox writing style. After all, I am left-handed, which positions me in the 10 percent rare or “odd” category of all human beings.)

Why Class in Corporate America Is Such a Taboo Subject to Consider, Let Alone Discuss

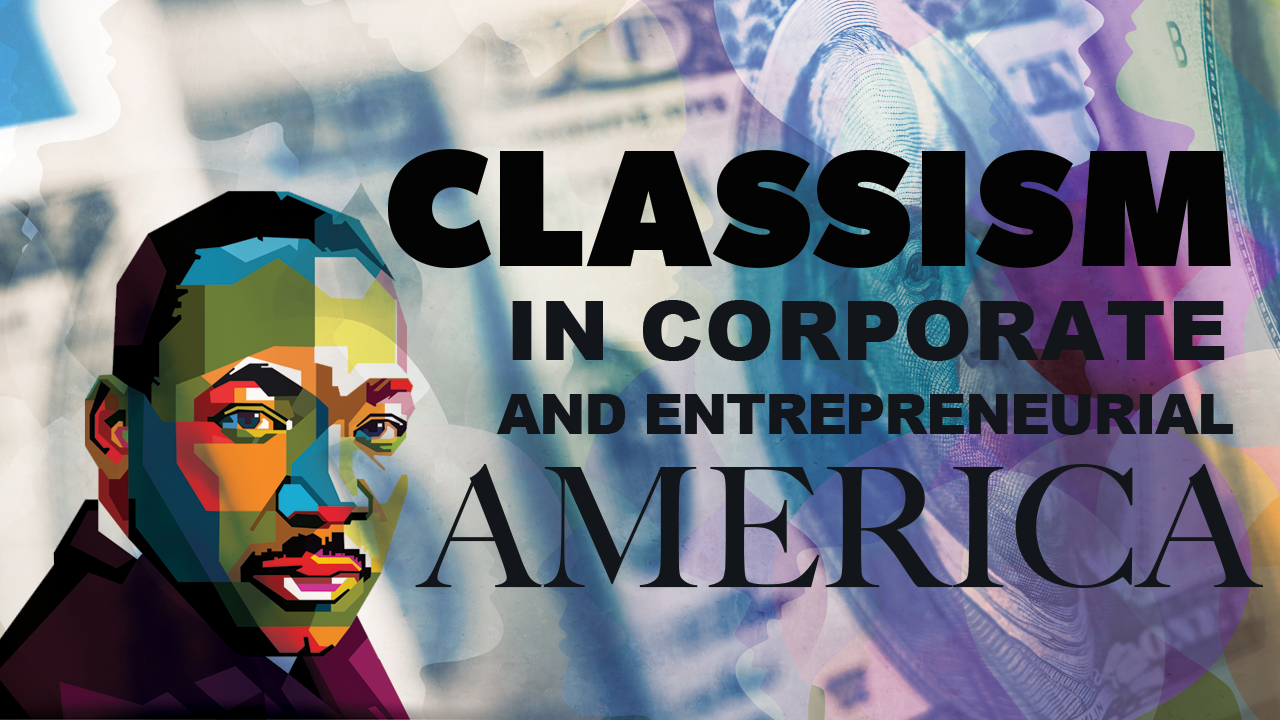

Behavioral finance explains the “what” in front of economic decisions, but psychographics uncovers the “why” behind their scaffolding frameworks. Here’s what I mean. How an individual, couple, or family spends, saves, invests, protects, or gives away money is largely shaped by their Sociopsychonomic filter. It’s both instinctive and intuitive, a foundational structure that serves as a default behavior pattern based on preconditioned mindsets around financial matters. And if a bad habit is hard to break, then an upgraded mindset is easy to keep. Let’s examine the word Sociopsychonomic, a term I coined that provides much-needed context to the classism controversy, and see where it shows up in corporate America.

The classism chasm in corporate America became more pronounced during the Covid pandemic, and quite frankly, hasn’t abated even as some semblance of normalcy returns. White-collar employees were (and many still are) able to work from the comforts of home, but brown-collar or base-level employees didn’t have this luxury, especially those in the hospitality, restaurant, and leisure sectors. In fact, many of them were let go. Those at the top of the economic food chain invested and profited greatly in a rock-bottom stock market, while their struggling peers took on more debt to stay afloat. Low-income wage earners who did keep their jobs were pressed to find alternative childcare arrangements when schools shut down, minimize stress in a stressfully chaotic living environment, and had to do significantly more work for less pay (what choice did they really have?) The poverty tax is glaringly obvious during times of local, national, or global turmoil. The next crisis — just around the corner — will be even more burdensome for them. Of course, the middle class (aka blue-collar workers) suffered considerably as well in making ends meet during Covid. They had to work two or three jobs, max out their credit cards when available credit was drying up, and/or borrow against their retirement accounts just as the stock market plummeted.

Why the subject of classism isn’t addressed inside the workplace might have a lot to do with the uncomfortable nature of social class dynamics in America. Favorable parking spaces, flexible schedules and accommodating work environments, and higher salaries (but with greater responsibilities) aren’t the only distance factors enjoyed by white-collar employees, also known as privileged lane runners. They are often viewed as the firm’s intellectual asset providers and value-driven creators by shareholders, board of directors, clients or customers, and even among their lower-salaried colleagues. This pecking order of importance isn’t a figment of imagination; many blue- and brown-collar workers express their concerns in feeling underrepresented in matters related to their overall contributions and self-assessment critiques. In-house surveys and DE&I programs rarely address the classism problem. In an interview, John H. shared with me, “This is exactly how I feel, and many other work peers who are in the same boat. As a blue-collar employee, I just don’t think my voice is being heard or valued. We have thousands of workers at this company, but only a few have the ear of top management.”

What many privileged lane runners fail to grasp is this: the employee flow charts or hierarchal structures in which they oversee has birthed and bred segregated groupings by virtue of shared (really, “felt”) oxytocin connections. White-collar employees typically associate and congregate with peers who tend to look, think, and/or act like them. The same can be said for blue-collar employees as well as brown-collar or base-level workers. Work environments are quite cliquish, this based largely on comfort rather than convenience. In other words, where colleagues feel they stand within an organization can mirror how they navigate occupationally and opportunistically, or even who they sit with in large (or small) group settings.

Whenever I’m invited to present, I usually walk around the room and greet a few employees prior to my speech, asking these three questions, with an inviting smile of course: Who do I have the pleasure of meeting? What is your role with this organization? How can I assist you today inside and outside the workplace? Obviously, correlation doesn’t equal causation but it should lead to contemplation. Here’s what I’ve observed. A predictable pattern often emerges as random seating is occupied by familiar faces, lane groupings, and employment positions. Even when arriving early, many brown-collar employees tend to sit on the periphery or in the back, blue-collar employees in the middle, and white-collar employees (or those with C-Suite aspirations) toward the front. Where they sit is known, but the “why” is not. I can’t share all of my secrets for “free,” but a deep dive into neuroscience and biochemistry will provide many cues and clues.

How Do Lane Groupings Cope with an Uncertain Financial Future Inside and Outside of Corporate America?

Take a look at the condensed chart below from our Lane Change U holistic development website. What piques your curiosity about a particular lane grouping? Which group(s) do you identify with personally, professionally, and/or philanthropically? Where am I missing or hitting the mark in my assessment of lane groups? How can this information help you relate better with your colleagues, customers/clients, or community partners? Why do you think classism is so difficult to discuss inside or outside of corporate America?

With a global geographic template, Lanes 4 and 5 are best equipped to deal with the unpredictable state of world affairs. Contingency planning or strategic forecasting is their domain, where the impact of international events or catastrophic crises seldom catch them off guard. They are proactive planners, lanes 3 and 6 reactive planners, and 1 and 8 bioactive planners. Proactive planners have a system in place to handle unforeseen events, a team of professionals who can assist them in making the right moves from a holistic vantage point. This doesn’t eliminate unforeseen problems, but can invariably diminish the effects of mental and emotional stressors in dealing with circumstances beyond their control. Reactive planners, lanes 3 and 6, respond to unexpected events or setbacks using their own devices but on others’ terms. In other words, their tightrope journey is often missing a corresponding balancing bar (which lanes 4 and 5 do have) to navigate an ever-changing, global landscape. The safety nets leveraged by lanes 3 and 6? You guessed it, unions, political parties, and their commendable work ethic. Bioactive planners have to feel a certain way before they take (or fake) a definitive course of action. Thus, they are more prone to displaying false-start tendencies in their life race while passing along the baton of emotion-guided behavior patterns to their legacy followers. World affairs disproportionately punish lanes 1 and 8 more than the other lane groupings; they’re often indifferent or oblivious to what happens around the globe. No matter the lane grouping, effective planning provides options and opportunities to capitalize on — instead of being punished by — the unpredictable state of world affairs.

I won’t explain in great detail the “why” but will express the “what” in regard to three class-related phenomena inside corporate America. Workers from the underdog lanes, especially black and brown employees, contribute significantly less to their 401(k) plans than other lane groups. A company or employer-sponsored match is technically “free money,” so why are they so reluctant to participate? Might it have a lot to do with their limited incomes? Perhaps. Could the primary reason be that investing, given the odds at play, is considered a close cousin of gambling by this demographic? Maybe. How about the unfamiliarity with wealth-building principles that are foreign to their way of thinking? Possibly. One thing is certain: They believe a bird in a hand is better than two in a bush.

For comfort zone lanes, the middle class, why do they treat W-4 withholdings as a forced savings vehicle? Providing Uncle Sam with an interest-free loan, returned in the form of a tax refund, offers peace of mind to middle-income earners. Since many of them take the standard deduction instead of the itemized deduction on their tax return, they could reduce their W-4 withholdings throughout the year (at the start of a given year) and use these “extra funds” to invest in the stock market, start a side business, contribute to a child’s 529 college account, reduce interest-bearing debt obligations, or apply them toward a real estate investment fund (which happens to be a comfortable place for the middle class to invest given the tangible nature of land or property). Like most things in life, this lane grouping’s primary concern is quite clear: they only want to deal with what’s in front of them. Right now is here; the future is not. Their focus is most content in the present moment.

Lastly, inside lanes of privilege do tend to suffer (among others) from one noticeably glaring drawback. They are often quick to conclude that a simple formula is the key to closing the wealth gaps in America. Do A + B + C to get D. Voila! Unfortunately, classism and the differences among lane groupings, as well as the subsets within them, are quite nuanced. Employees from traumatic backgrounds usually have compromised circadian rhythms, which regulate, like a symphony conductor, nearly ever system in the body. If a life is out of rhythm, then so will one’s finances, economic compass, and monetary filter. By all means, blue-collar employees can stay true to their down-to-earth roots. However, they do need a white-collar, wealth-building mentality as promises owed by employers turn into obligations not kept to employees. Gone are the days of guaranteed pensions, lifelong job security, and free health insurance (nothing is ever free!) When you’re at the top of the employment hierarchy, it’s easy to assess things from a 30,000 foot view. But the ground floor is where you/me/us can come in contact with common folk who are scared to death of what the future holds financially. Let’s help each other without pointing fingers in (but certainly at) the process.

A Chalkboard Scratching Moment That Still Gets Under My Skin

I’m showing my age (might you be as well?), but I remember those ear-piercing moments when teachers, back then, female in the majority of cases, would rattle my inner core. How so? Their nails would, out of nowhere, scratch the chalkboard while writing incursive. Several of my classmates, including me, would immediately cover our ears as the penetrating sound sent the alarm bells ringing deep inside our gut. We were caught off guard and did our best to mitigate the effects of that screeching, attention-deflating noise. Ironically, our sense of wellness is largely produced in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract through the serotonin pathways. Over 90 percent of the production of this feel-good neurotransmitter is manufactured naturally in the GI tract, with favorable or unfavorable sounds, words, and foods boosting or busting our feel-good meter. And every time someone uses the term “financial literacy,” especially in the world of banking or financial services, I am reminded of those sickening, chalkboard-scratching moments in elementary school.

A few years ago, I had a meeting with a banking CEO. We discussed a win-win-win partnership to close the wealth gap societally and organizationally; his bank, our nonprofit, and the community footprint in which his institution served would all benefit. The following account with the banking CEO crystallizes my thought process on financial literacy. (Yes, it hurts to even write the term, let alone revisit a conversation about it.)

Me: What are your thoughts on where we stand in closing wealth disparities here in Central and Appalachia Ohio?

Banking CEO: Well, the first step we need to take is to improve the financial literacy of disadvantaged communities. Without this knowledge, they will always be playing catch up. Right?

Me: Well, with all due respect sir, I have to challenge your conventional framework in a critical area.

Banking CEO: (leaning back while creating distance between us) Really, in what way?

Me: (showing noticeable agitation) You see, the term ‘financial literacy’ is fraught with all kinds of negative connotations. To state matter of factly that someone, or, in this case, a community, needs literacy is to imply that they are or could be viewed as being illiterate.

Banking CEO: Wow, this perspective never crossed my mind.

Me: As someone who grew up fatherless on welfare in a low-expectation environment, I take tremendous offense to this term. Capability is one issue, but accessibility is something altogether different.

Banking CEO: What do you mean?

Me: Vulnerable communities are capable of learning anything, so long as the messenger communicates a relatable, palatable, and identifiable message in an easy-to-understand language. When this occurs, foreign concepts come alive; the veil of secrecy has been lifted from their eyes. More importantly, these individuals feel empowered. In fact, they’re now granted access or entrance into a new world of upgraded words. This is how we can partner to change lives and legacies one family or inner-city community at a time.

Banking CEO: (breathing a sigh of relief) Makes perfect sense to me, and from this day forward I will never use the term ‘financial literacy’ again. Mark my word.

Me: Thank you.

Take your pick. Financial education. Financial wellness. Financial empowerment. Financial success. Financial fitness. Financial freedom. Financial stewardship. Economic mobility. Economic wellbeing. Economic health. Economic harmony. Economic viability. Fiscal diligence. Fiscal resilience. Fiscal sustenance. Wealth security. Wealth parity. Wealth privilege. Knowledge currency. Please use any of these terms interchangeably when advocating on behalf of underserved populations or disenfranchised groups, but not financial literacy. Literacy, as highlighted, connotes a lack of knowledge about a given subject, being unskilled in a particular area, or worse, someone who is incapable of learning due to underlying deficits, deficiencies, or defects. See how problematic financial literacy is? Semantics matter a great deal when ________ ________ (you choose) is on the line personally, professionally, or philanthropically. I cover the phenomenon of classism in great detail in my book, Sociopsychonomics: How Social Classes Think, Act, and Behave Financially in the Twenty-First Century.

In closing, economic mobility is arguably the most important skillset a young (or even seasoned) employee must develop in corporate or entrepreneurial America to survive, let alone thrive in an ever-changing and dynamic landscape. Its pillars include the ability or conviction to live out one’s values, the agility or condition to labor in one’s value proposition, and the affinity or connection to lead with one’s invaluableness. Those who do all three equally well will be coveted in boom or bust labor market cycles. These outlier attributes are not native to a particular ethnicity, class, or gender, but they can certainly help any employee run a life race or complete a legacy journey with grace, the love kicker. When you add value consistently and efficiently — regardless of the task or activity — people take notice. Economic mobility is a rocky road in corporate America. The terrain can be remarkably treacherous; its pathways quite taxing and exhilarating, and beneficial outcomes anything but a sure bet. In due season however, the work involved will eventually be rewarded. The Law of Compound Interest wouldn’t have it any other way.

Related Articles

Nothing found.

Contact

Connect with us.

If you would like to participate in the Post-Assessment Survey of the MLK Series on Race in America, please send an email. I look forward to speaking with you.

MLK Installment #4

Lawrence Funderburke

The DE&I (and B) Conundrum: What Initial Is Missing from the Connectivity Equation in Corporate America?

DE&I (and B), which stands for diversity, equity, and inclusion, and belonging. Some employees love the initiative, while others despise it. As a mentor of mine shared, who is arguably the most respected black woman and thought leader here in Central Ohio, “This is a movie that we see every 10 or 20 years. I’m hopeful but a little leery on what gaps DE&I programs will actually close this time around.” She added, “Even though it’s a different version of the same movie, we still have to take advantage of the opportunity to move the needle forward for black and brown employees as well as for women and other underrepresented groups. And what’s different today than in decades past is the number of organizations who are on board. Where the ship sails, time will only tell in regard to meaningful change.” One thing is certain: DE&I isn’t a passing fad; it’s likely here to stay, with ESG (or environmental, social justice, and governance) serving as a companion anchor. But the question to ask, “How will organizations create an atmosphere of growth where every employee benefits, not just a particular carve-out group?” In this fourth installment of the MLK series, I’ll present a fair-minded and sensible approach to making all feel welcome inside corporate America, including minority and majority groups alike.

Which letter, starting with “A,” would represent the next addition to the DE&I plus B equation? How about accommodation? Might appreciation work better? Best of all, should acceleration be pushed to the front of the selection line? Accommodation. Appreciation. Acceleration. Not in corporate America, but AAA can save the day when a vehicle emergency occurs. As a proud, card-carrying member of AAA, help is only a text or phone call away. We’ve all been there as seasoned drivers, or witnessed it while driving on the highway, a car that is stranded on the side of the road. Whether it’s AAA or another roadside assistance operator providing a battery charge or fixing a flat tire, this service offers members the convenience — really peace of mind — of safety and security. And this is where we are today in corporate America, and society overall, in need of a different kind of roadside assistance. Now, we can continue to add letters and advocate for top-down change, but rarely do we consider the urgency of bottom-up transformation. Here’s what I mean. Nothing changes corporately until we diversify individually. We often confuse change happening around us for growth occurring within us. And this is the classic definition of insanity, where we expect a different result using the same, tired process. Progress does not occur unless process is upgraded. And it’s easy to point your finger at someone, some thing, or some system to change. Inevitably though, you have three pointing right back at you. When we deal with ourselves three times more than someone, some thing, or some system, change will be an organic and deliberate endeavor. If you accept this premise, then what catchall A-word would best serve DE&I purposes? I propose “accountability,” of the grace-led kind.

You see, DE&I won’t work without accountability, and it can’t survive without grace. I often tell my children and those under my stewardship care, “I love you enough to hold you accountable for the change that needs to take place in your life, legacy, and leadership pursuits.” Leading with love — the calling card of grace — doesn’t minimize responsibility. However, it does soften the blows of personal and professional growth. Not just those who are in positions of power, privilege, and prominence, but everyone needs to change. Be on the path of change before you create changeable pathways for others. A lack of accountability is akin to a team requiring that only one or two players improve their skillset, while allowing the other players to maintain who they are. This team will not only struggle, worst still, it’ll likely suffer as well. When players, coaches, and support staff are not held accountable, distrust creeps in and bonding moments head out. That oxytocin connection, which keeps a team unified, is short-circuited or severed altogether. Either way, distance is created. Handshakes, chest bumps, and other encouragement gestures subside, while finger-pointing picks up as players become more self-centered on the field or court. Talent can only carry a team so far; camaraderie is the key to sustainable success. This oxytocin-busting dynamic happens in corporate America, too. Now, teams and employees can still do their jobs, but that bonding, trusting, and loving connection will be lost or out of tune. Productivity can be maintained, but it likely won’t be enhanced. No rhythm, no rhyme. Work is just about a paycheck with benefits. Nothing more, nothing less. Does this describe you or your organization?

Why the Pros Are Not Joes and How You Can Imitate Their Growth Trajectory, Too!

Change — meaningful and measurable growth — is obviously difficult for a lot of people to pull off. Now, change is uncomfortable, but it’s absolutely necessary. The only way an individual can change is through discomfort. No growth can take place without some type of friction, and this friction involves consistent and deliberate action steps. Employees have to change, but they need to grow into their progress through an upgraded process. Enter the shot clock and game clock. If a team fails to shoot the basketball within 30 seconds in college and 24 seconds in the NBA, then that team loses the possession. And squandered growth opportunities are lost everyday in corporate America when workers check in for the day but check out on personal improvement and professional refinement. With the game clock, a team sets the tempo early and executes the game plan accordingly, depending on who is on the court in the first or second half, with adjustments being made during halftime. Herein lies the problem. People may want to change, but they don’t know how to change, who can assist them with the change, or where change needs to take place first. Organizations introduce their employees to DE&I concepts, many of which are theoretical in nature, but how do they create an environment where growth is dynamic and automatic? And who is responsible for initiating and monitoring gains personally, professionally, and philanthropically? If any of these are MIA, then holistic change will be DOA (dead on arrival). One more point: Accountability must be a two-way street or else it leads to a dead-end road.

The most diverse player or skillset on the basketball court is the small forward. This is why LeBron James and Kevin Durant (and Larry Bird) are considered the standard by which all small forwards are compared. Small forwards can create offense for themselves and others. They can shoot and score when needed. They can rebound and play defense. Small forwards often have intangibles that go unnoticed to the casual fan, such as their leadership credentials and allyship capabilities. They have the athleticism and quickness to play on the perimeter or wing, just like point guards and shooting guards. But they also display interior skills where they can post up, score inside, and rebound on the offensive and defensive sides of the ball. They often have the size, strength, and stamina to battle inside. In fact, NBA teams typically break down the development game in practice into two groups. One group consists of “smalls.” These include point guards and shooting guards. (I realize it’s an oxymoron to call a 6’6” guard “small.”) The other group is the “bigs,” which consists of the power forwards and centers. And depending on the size and skill level of small forwards, they will be asked to join either the smalls or bigs. Now, some small forwards have the same height as the interior players, but they also display the quickness, athleticism, and skillset of point guards and shooting guards. In other words, their diverse skillset serves as a bridge between interior and perimeter players. Lastly, the first step of change is to take a personal inventory assessment (PIA) or internal scouting report (ISR). Without a frame of reference to track where you currently stand, growth will be a fleeting proposition. I cover this developmental template in my book, Momentum Power Play, as well as in Huddle Up Coaching presentations.

“I Can’t Put My Finger on It, But I Will Do Plenty of Finger Pointing Until I Do!”

DE&I is not a perfect system. It has inherent flaws that are beyond the scope of this article, including the following unintended consequences: the promotion of gender stereotypes or racial archetypes (rather than the absolution of them); the propagation of hand-up programs that many employees view as handout promises; and the propitiation attempts to right the wrongs of historical injustices in a corporate setting through referee means and referendum measures, among many other side effects. I get it. Skeptics of DE&I initiatives offer legitimate concerns, critiques, and complaints. Unfortunately, they’re too afraid to voice their displeasure out loud in a public setting for fear of reprisal. Simply put, they don’t want to be labeled “out of touch with the times,” “outcome puritans,” or worst, “outed bigots (aka in-the-closet racists).” Those who are out of touch with the times can’t, or simply won’t except the fact, that America is changing. Now, we can argue about the changes that have taken place, whether good or bad, or somewhere in between, but things have certainly changed and are changing inside and outside of corporate America. Outcome puritans, a term I coined, want to see a return on investment (ROI) with racial connectivity offerings but without a commensurate OCI — ongoing capital infusion. They form committee after committee, facilitate breakout session after breakout session, and send survey questionnaire after survey questionnaire, but nothing ever gets done. Teasers who don’t like being teased. Box checkers who inevitably and regrettably box themselves in. All talk and no action but plenty of reaction when an optic-driven racial incident occurs that sparks a controversial protest or countrywide movement, especially during Black History Month, around Juneteenth, or on the anniversary date of a social justice martyr’s death. I hope this doesn’t sound like your organization. Finally, outed bigots or in-the-closet racists can’t be defended. They often say the wrong thing in the wrong way for all the wrong reasons. No example needs to be provided because their folly is evident and quite varied, including their unfiltered coarse putdowns — really slam downs — and demeaning jokes about minority groups. Absent character, they morph into caricatures of backward thinking, reminiscing about the “lily white” glory days of Maw and Paw television sitcoms, protecting their good ole boys network (on both sides of the political aisle), and maintaining the status quo of their power structure within the corporate America hierarchy. Nothing’s funny when people choose to be that ignorant, okay, mindlessly inconsiderate.

A close friend of mine, who I’ll refer to as Joe, has utter contempt for DE&I initiatives. He is white, conservative, straight, Christian, and affluent. Are you profiling him right now? Don’t fall into the judgmental trap! You see, he is entitled to his opinions, but he can’t pass them off as facts. And he shouldn’t be ostracized or demonized for having divergent viewpoints. Why can’t we agree to disagree without engaging in blaming, framing, and shaming tactics? A few months ago, he and I had an unprompted discussion on DE&I. Here is part of our conversation:

Joe: By the way, I heard you were working with companies in the area of DE&I. Is this true?

Me: That’s right. What are your thoughts? (Open-ended, counter-serve questions create a level-playing field when hot-button topics are discussed.)

Joe: (laughing) Honestly, I think it’s a sham, or better yet, a scam. I don’t see any value in offering DE&I programs in the workplace. They don’t make any sense to me; they’re also a waste of time and money. Besides, they’re incredibly divisive, pitting one group against another group.

Me: (in a firm but non-threatening tone) Do you honestly believe that things inside and outside of corporate America are where they need to be?

Joe: (pausing) Well, no I don’t, but …

Me: (interrupting him as he gathers his thoughts) C’mon now. Doublespeak isn’t good here. You agree that problems exist and then quickly pivot to the proverbial ‘but.’ This, my friend, should lead us to a teachable moment. First, this type of thinking assumes that time has healed the historical wounds of racist ideology and racial orthodoxy. Second, our world would be in a much better place if society simply practices what it preaches.Third, external change is led by internal transformation — not the other way around. And if you’re against DE&I, then what are you for?

Joe: Alright, I see your point.

Notice that I reaffirmed our friendship and gave Joe every opportunity to play offense rather than pay defense, yes, pay defense. Defensiveness is costly. The brain goes into emotional overdrive instead of rational positioning. Blood pressure rises, thanks to cortisol and adrenaline surges. Breathing becomes more shallow and pronounced as airflow constricts. And of course, tribal affiliation talking points are staunchly defended. The result? Baseless (or boastful) allegations, combative bickering and contentious bantering, or even physical altercations are the default, usual suspects when uncivil dialogue goes off the rails. Will the real adults please stand up, because the cardboard cutouts in the corner don’t count? Yes, I did interrupt Joe when his pause segued into that classic, Double Jeopardy countdown music. Teachable moments serve as connection opportunities — not recruitment tools — independent of a person’s social, satirical, or sexual orientation cues. Allyship is a partnership, a pathway for authentic leadership to flourish. Even with people who don’t look, think, or act like you, take the high road when you’re dragged through the conversational mud. Adding grace and accountability to the discussion mix can clean up any mess. And don’t forget to separate the person from the problem. Now, problems are created by people, and problems get fixed when fixated people change their fixable perspectives, which should occur by choice, not force. Got it?

In conclusion, let’s recap some of the themes highlighted in this article on DE&I (and B). Truth be told, critics and beneficiaries alike are leery of diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. Both camps offer up valid reasons that support their premise. Detractors believe carve-out programs cause more harm than good. They assert, “Isn’t diversity best served through unity, rather than the divide-and-conquer strategy of unity through force-fed diversity?” I’d argue that diversity is evident when unity reigns (a la winning sports teams), and oxytocin-led unity is the inevitable byproduct of holistic diversity, where diverse mindsets, skillsets, and subsets are wholeheartedly appreciated. Now, those who do stand to benefit from DE&I offerings don’t want to be viewed and judged as perpetual charity cases, nor do they want to be denied access to opportunities and options that have been traditionally earmarked for white men in the PPP club (or the power, privilege, and prominence clubhouse). Optics do matter, but semantics should matter more. If an organization preaches diversity, then its practices should align without alienating or denigrating those who fall outside the carve-out group ecosystem. See the Catch-22 that both camps, and the organizations that employ them, find themselves here in 2023? The win-win solution to the DE&I (and B) conundrum is this: Create an emotional safety net where minority and majority groups can both grow into their graceful change through self-imposed accountability measures. Stay tuned for the last installment of the MLK Series on Race in America: mobility. And yes, as a certified financial planner (or CFP), we have more of a class issue than a color beef. I’ll prove it.

Related Articles

Nothing found.

MLK Installment #3

Lawrence Funderburke

The Justice of Just Us: What Does It Mean? Why Does It Matter? Who Stands to Benefit?

No justice, no peace. It’s a phrase we’re quite familiar with, given its racial, social, and political, pre-Covid overtones. Dr. King stated, “An injustice anywhere is an injustice everywhere.” Profound and provocative at the same time. When it comes to justice, black and brown Americans keep asking, “Why is it just us who feel this way?” Just us being scrutinized by law-and-order referees while sporting our permanent away uniforms. Just us being profiled or stereotyped while driving through upscale neighborhoods. Just us being seen as the proverbial window shoppers while walking around high-end department stores. Just us getting the short-end of the opportunity stick outside the workplace. Just us being passed up on a promotion inside the workplace as an over- or under-qualified job candidate, or finding ourselves as that lucky, “handpicked” actually, racial-quota charity hire. Bronze (Indian) and beige (Asian) Americans are also raising their voice of concern. On the higher-ed admission front, they’re asking, “Why is it just us, or our kids, who are unfairly being punished by top-tier colleges and universities because we overrepresent the minority-student population?” And blanco Americans in rural areas — the invisible white class — have equally, if not worse, life outcomes as inner-city communities of color. Their voice needs to be heard and respected just the same. A justice-just us framework will be explored in this third installment of the MLK series. Buckle up; it’s time to go on another bumpy ride.

A Rogue Teacher on a Seek and Destroy Mission

I don’t like living in the past. But for illustrative purposes, sometimes it’s necessary to go back (but not stay) there to explain how we arrived here. The year was 1981, not 1881. I was a fifth-grader at Westgate Elementary School. Across the country, inner-city blacks in the 1970s were bused to better performing schools in predominately white neighborhoods. Institutional racism is one thing, but educational injustice is a whole ’nother ball game. We, Americans in general, can have a civil debate about what fundamental rights we’re owed and who should pay for them. However, every child — regardless of race, gender, or economics — deserves a quality education.

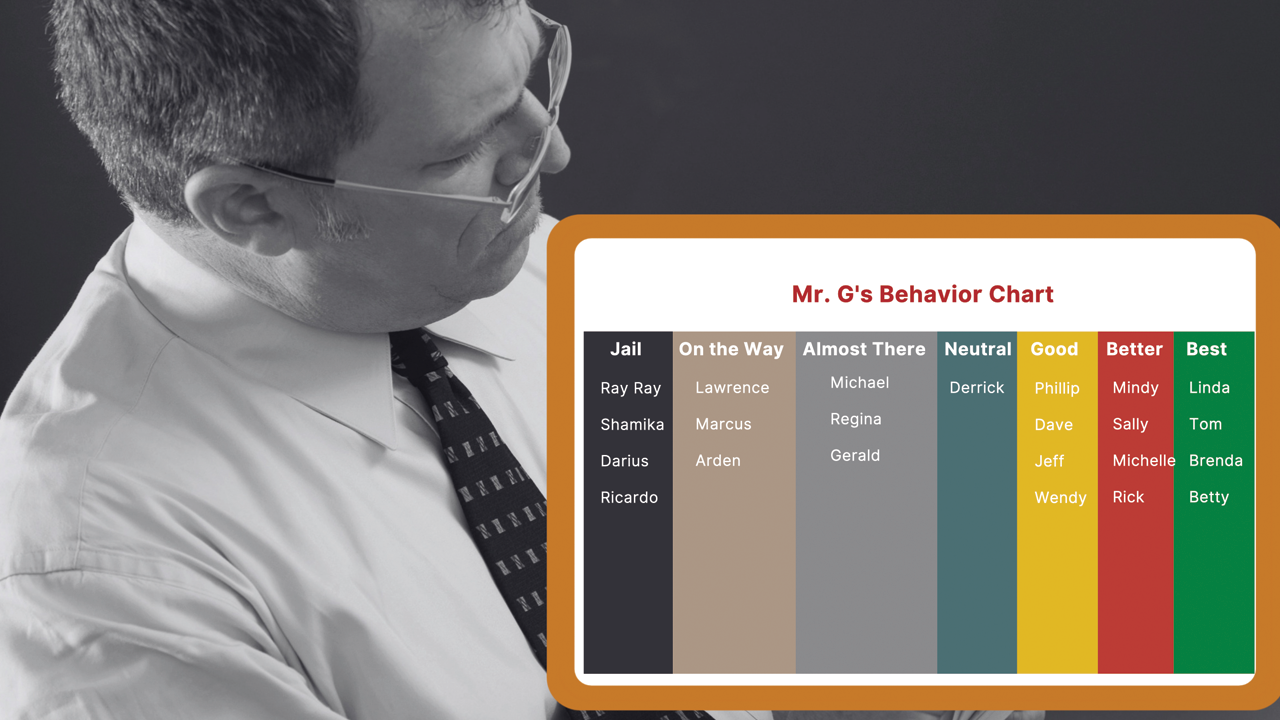

I, along with several classmates, were victims of academic bigotry over the course of an entire school year. Mr. G, one of my elementary school teachers, was an outlier. In no way did his unconscionable deeds cast a dark cloud over the wonderful experiences I had overall in the classroom as a kid being taught primarily by white teachers. The color of their skin didn’t matter to me but their commitment to my educational development did. Ready for this? Mr. G had a color-coded chart in his classroom that rewarded or punished behavior based on his jaded worldview. He served as a judge, juror, and probation officer, whether or not the sentence fit the crime. Looking back, I don’t know how he was able to get away with his demented experiment. Three decades later, I was told by a colleague who worked at the school with Mr. G that he taught with a racial bias. Duh, thanks for the heads up now.

Mr. G would advance a student to the right side of his chart — “good,” “better,” or “best” — for appropriate behaviors. These were the upstream, free-flowing conduct blocks. Questionable behaviors were demoted to the left side of his chart, the downstream blocks, including “on the way,” “almost there,” and for many of the black students in class, “jail.” Think about the seeds Mr. G was trying to plant in our minds: intellectual inferiority, criminal susceptibility, and educational incapability. Latitude was given to the white students for minor offenses such as talking in class, chewing gum, or horseplay, but very rarely did he extend any grace to black students. His methods emitted a foul odor of unfairness. And he wore this putrid cologne every day to annoy us even more. His merit-based behavior system, which he took great pride in, allowed some students to enjoy extra perks — treats that he brought to school or a special recess granted to “worthy scholars” at the end of the school day.

Mr. G’s Behavioral Chart

Mr. G didn’t particularly like me: I didn’t fit his sick narrative. Poor black boys from broken homes are supposed to be academic casualties, incapable of adding anything substantive to the educational experience. I could go on and on about the misdeeds of Mr. G — making us stand in the corner of the room with our hands up and feet spread apart as though we were being (or one day would be) arrested, placing our desk out of view behind the coat wall, or slapping our hands with a plastic ruler — a man who was in his mid-to-late 50s nearing retirement back in the early 1980s, which meant he would have likely come of age during the racially divisive era of the 1950s and 1960s. He was Archie Bunker, of All in the Family fame, masquerading as an educator. To imply that our path in life would inevitably lead to prison (in all its forms) is mind-boggling for someone who presumably took an oath each year to educate all children — black, brown, or white — in Yankee territory.

I am not sure Mr. G is still alive, but I don’t hold any animus toward him or his offspring (since the apple doesn’t usually fall too far from the tree). Extended mercy is for my benefit, not his. No easy task when you were intentionally and systematically abused. But you know what’s even more sad about the story. White teachers and school administrators didn’t intervene on our behalf. They were aware of Mr. G’s methods and disdain for the black students who had invaded “his white, middle-class comfort zone” on the hilltop. They allowed Mr. G’s racist attitudes and sinister actions to create a toxic learning environment with legacy implications. For this reason, they were equally guilty. Affecting and infecting the fragile minds of poor black kids who were (and still are being) written off as hopeless misfits is abominable. Even today, many stand by and do nothing about academic gaps, wealth inequalities, mentoring shortfalls, incarceration disparities, economic vultures, and food deserts (or the lack of healthy food choices) that are glaringly obvious in distressed, urban communities. Failing those Americans who need every ounce of positive momentum they can secure to have a legitimate shot at life is un-American. What can you do at a grassroots level to be a solution and not an accessory to these inhumane crimes?

“How Many Strokes Are You Giving Me?”

I enjoy playing golf. The camaraderie with other golfers. The beautiful landscape. The clarity and creativity of thought, which immaculate greens tend to generate, and according to color theory, may explain why so many business ideas, partnership mergers, and handshake deals take place on the golf course. It’s a game that I’ve attempted to play for over 20 years, thanks in large part to Tiger Woods. His ascendency in the late 1990s and early 2000s as the world’s best golfer inspired many people of color (POCs) to try their hand at a sport that was historically viewed as “the domain of privileged white men.” Speaking of hand, my handicap is an impressive 25. Don’t laugh. My athletic skills are such that I will hit my fair share of Tiger Woods shots. But as a golf hack, my Tiger Whoa Whoa shots keep me humble when they venture off the fairway, deep into the woods. And yes, given my impoverished upbringing, I’ll risk catching poison ivy to retrieve lost golf balls, even with two dozen of them in my bag. Now, I’ve had plenty of expensive and time-intensive lessons through the years from great coaches, but for some reason, my handicap hasn’t budged much. Perhaps I need to spend more time practicing and playing to master a consistent golf swing. Then again, so much can go wrong trying to hit a tiny ball using custom-made clubs with extensions to accommodate my 6’9” frame. (I recount this story in greater detail in the book, Sociopsychonomics: How Social Classes Think, Act, and Behave Financially in the Twenty-First Century.)

If you’re not familiar with this sport, a golf handicap allows amateur golfers — on any course — to compete against higher-skilled players. Golfers with a ‘high’ handicap, like me, are allowed a higher number of extra strokes over the course par. Those with a ‘low’ handicap tend to take fewer strokes to navigate the course (reference: fairwayapproach.com). In golf, a player’s handicap is a measurement tool to gauge skill level but not necessarily heart or intestinal fortitude. As a lifelong competitor, I’ll take the golf strokes and make the most of the opportunity, no matter who or what weather conditions I’m playing against on a particular day. The law of favorable averages (LOFA), or strokes of good fortune, eventually bend in the direction of those who have been shortchanged in life. That is, if they’re resolute in achieving better life prospects, legacy pathways, and leadership paradigms. They just need a few breaks for their opportunity ball to role in the equity cup.

Golfing aficionados engage, often unaware, in affirmative action practices every time they participate in the sport. Although not a perfect tool, a golf handicap bridges the gap between higher-skilled and lower-skilled players. And for some avid golfers with decent handicaps who are invited to play on a prestigious golf course at an exclusive country club by the host, a scratch golfer by the way, they’re quick to ask as tee time approaches, “How many strokes are you giving me today?” With affirmative action practices in higher education, “strokes” or special preferences are given to some incoming students who aren’t white affluent nor do they qualify as minority adjacent, or young people from Indian- or Asian-American backgrounds with impressive academic scores. Whatever caused or contributed to the academic gaps experienced by vulnerable POC students at the front end — a toxic environment, poor role modeling, negative peer influences, economic challenges, and/or revolving setbacks — let’s find a way to close them at the back end with a quality education, relatable tutors, career mentors, a meaningful degree, and beneficial networking contacts secured in a higher-ed (or trade school) setting. Admission quotas are fraught with perils, but at least they give those on the fringes of society a firmer chance to move up a social class or run in a better opportunity lane.

The Collaboration Arena: A Judgment-Free Zone for Change

Allyship was the word of the year in 2021, this according to Dictionary.com. It’s actually an old school word for a new school world. Simply put, it’s sticking your neck on the line for others outside of your affinity group, kindred connection, or tribal affiliation. White abolitionists who were instrumental players in The Underground Railroad movement risked their lives and livelihood for black slaves. Allyship is about honor, not duty, understanding, not guilt. Allies find ways to right the wrongs of injustice without pointing fingers — the blaming, framing, and shaming contest. When you point a finger at someone, some thing, or some system where disprivilege or inequity occurs, guess what, you have three pointing right back at you. And if you’re down with The Three Times Rule, then you are keenly aware that a change agent must transform into something better before creating changeable pathways for someone else. Got it? The Collaboration Arena practices holistic allyship, really an accountability partnership rooted in goodwill, for white men who hold positions of power, privilege, and prominence.

On January 28, 2021, I hosted a dinner for 20 white men at the C-suite level. On my own dime and time, while also being cognizant of Covid protocols, I invited them to a three-course meal at Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse. Now, defense is great for sports team. However, offense is how you keep players excited about the prospects of winning. And yes, white men in positions of influence will be instrumental in the outcome of the racial connectivity game. Only two blacks were in the room, me and the moderator, Steven Davis, the former CEO of Bob Evans restaurants. I spoke passionately and persuasively for about 10 minutes at the onset — using the language of sports analogies as the backdrop — to set the tone for the evening. I opened with these comments, “Gentlemen, you don’t have to sit down, but you do need to scoot over. It’ll be tight, but there’s enough room in the opportunity front seat for those who don’t look, think, and act like you.” I added, “This is our locker room moment. Let’s talk about the game that you have the power to influence as opportunity coaches.” That evening we had some candid conversations on what needs to change in corporate settings and inner-city communities. No one got a free pass. How did we pull this off? Simple. We created an environment where an emotional safety net was present before they even arrived at Ruth’s Chris. Had this not been the case, they would have declined the offer. Straight, conservative white men in C-suite positions have a target on their backs. They’re at the bottom of the proverbial football pile; they now know what it’s like to struggle breathing, figuratively speaking that is. Instead of pilling on, I am pulling off. Working with them through reasonable measures as opposed to working against them constrained by unreasonable metrics was (and still is) the key to helping companies hire qualified POCs through dignified gestures. Diversity for the sake of diversity is a bad thing because it’s based on a zero-sums game: whites regrettably lose and people of color inevitably win. But diversity that appreciates the richness of other cultures, classes, and communities creates a dynamic and panoramic ecosystem where everyone has the right but not the guarantee to flourish.

Let’s close on a positive note. I was invited to a political gathering several years ago (and haven’t been invited back since) to discuss wealth disparities in the black community. Famous dignitaries, CEOs, political figures, celebrities, and other former pro athletes were in attendance. Panelists were given six minutes to share a message that resonated with the audience, most of whom were POCs. My mic drop moment came when I shared this timeless truth at the onset to free black folk, financially or otherwise, from the shackles of America-induced trauma: “We can’t hold whites hostage for all of the historical injustices that have been perpetrated against our people. We must let them go for the sake of our legacy, not theirs.” Roughly half of the attendees agreed with my advice in principle, and the other half rejected it in practice. Forgiveness doesn’t mean blacks must forget about slavery, anti-literacy laws, lynchings (almost 6,000 documented cases), Jim Crow, segregation, housing discrimination, and other ancestral wounds too numerous to mention. No, but we do need to forgive while holding white America and ourselves accountable for the change that should take place. This ongoing choice — a settled decision without a cutoff switch or expiration date — rests in our hands. Choosing to forgive can’t be a head or heart matter; it’s not always going to make sense or feel right. But it must be a hunger initiative to feed and nourish the human spirit. And this, my friends, can’t occur without the accompanying payment of grace, a formidable ally that can pay dividends for generations to come.

GRACE + ACCOUNTABILITY = RACIAL CONNECTIVITY

This simple formula isn’t easy, but it is absolutely necessary to move our country forward. Diversity, in the form of cultural capital, is next up in the MLK series.

Related Articles

Nothing found.

MLK Installment #2

Lawrence Funderburke

Equity vs. Equality: What Do People of Color (POCs) Really Prefer and Desperately Needs

In the first article of this installment series celebrating the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, I discussed the hot-button topic of privilege. That controversial trend line will continue here, albeit at a much steeper grade. Before getting started, I have a confession to make: I am a man without a political party. I grew up rooted in Democratic ideology as a fatherless welfare recipient (I still carry around a three-decade old food stamp in my pocket!), converted to Republicanism, more precisely, an in the closet Republicrat, as a former and retired NBA player. But now, I find myself in political purgatory, disenchanted with the leadership and direction on both sides of the aisle as we, all of us, by and large, obfuscate the responsibility to play our part in helping all boats rise in every sphere of color-coded America. And yes, we must accomplish this arduous task TOGETHER without scoring political points in the process. A frank discussion and framework-driven game plan are essential — without pointing fingers — to move the opportunity ball forward for black and brown Americans who feel (and are being) left behind.

Let’s go deeper into the equality-versus-equity conversation. I conducted a poll in 2022 within my social circle across financial, professional, religious, gender, and even life-experience lines. The sample size was small: 50 African Americans. Now, we’re not as monolithic as some political pundits describe our race. However, most blacks working in the public or private sector over the age of 30 are Democrat (voting roughly 90 percent of the time for “the party of POCs”), incredibly resilient in spite of the obstacles behind or in front of us, a component of our ancestral DNA, and lastly, quite disillusioned by the chase. The American Dream has been elusive for blacks. We were, and in many cases still are (outside of collegiate/professional sports, entertainment, and politics) treated as third-tier citizens — whites, others, then blacks with ties to American slavery. We were promised 40 acres and a mule (stop holding your breath black folk!) We were emancipated as slaves in 1865, but how many of us live as truly liberated people in 2023? This is rhetorical; very few of us, though we make up approximately 13 percent of the population. As our revered echo chamber often likes to say, Jesse Jackson, “Keep hope alive.” Sounds good in theory, but what about in application? Hype is good (it brings awareness), hope is better (it breeds confidence), but help is best (it brands justice). Bring. Breed. Brand. Our reparation moment is now! We don’t want to be viewed as a perpetual charity case, but where’s our empowerment train? Enter meaningful dialogue on two contentious issues: equality and equity.

I texted this intentionally bifurcated, two-sided question to each poll respondent:

If you had to pick just ONE, would you as an African American prefer EQUITY (economic “skin in the game” in comparable or greater proportions than whites absent racial equality) or EQUALITY (racial parity into mainstream society to the same degree as whites but without financial equity)? Please explain your rationale.

Here are the results. Roughly 70 percent of respondents selected equity, and approximately 30 percent chose equality. (Unfortunately, the black experience in America has been fraught in making difficult choices within an either-or context, which may explain why we automatically default to this paradigm shaft, not shift, in matters tied to race.)

Not all are highlighted, but poll respondents shared the following explanations, insights, and comments. For the sake of brevity, I’ve taken liberty to condense some of them:

“I’m going with ‘skin in the game.’ Let me get the bread, the resources, and a better network, and I’m good. With street smarts, thick skin, and the right tools, and most importantly, the Lord Jesus Christ on my side, I can’t be stopped. And equity is my legacy game as a father of five!”

— J.T., Brother in the Struggle

“Equality for me because I’ve been in situations where white counterparts and I had the same rank, job title, and work responsibilities but I was paid less.”

— M.A., Teacher’s Aid (Public Elementary School)

“The answer has to be Equity! That is what was needed in the first place. Segregation is less of an issue when economic resources are plentiful in the black community. If you have equity, then you can eventually reach for equality.”

— L.C., Physician

“Equality for me. With this under your belt, you can create your own equity.”

— G.A., Barber

“Equity! Enough said.”

— News Anchor

“Equality. The equity piece is way too late for the majority of our people! We’re born without the silver spoon of family wealth — if you catch my drift. Equality is more achievable; it’s still a steep hill to climb, though!”

— R.T., Corporate Executive

“Equity dominates American financial systems in that money doesn’t see color, only the results of having it, or in most cases, not having enough of it.”

— G.L., Public Civil Servant

“This is tough; it’s a bit of a false dichotomy. Choosing one option assumes the other option is unachievable or false. With that disclaimer, I would cautiously choose Equity. In America, financial parity or financial excess allows for acceptance. While acceptance is not equality, I will take that, along with the money!”

— L.F., Attorney

“EQUITY. Equality simply gives you a seat at the table. But with equity, I have the ability to build many tables and create opportunities for others to succeed also.”

— K.C., Entrepreneur

“Equality has been more important in history to us because it’s the reason equity hasn’t been accomplished to a meaningful degree in the black community. We’ve never been seen as equal to our white counterparts, especially in corporate America. There was a time when we weren’t even considered a full person, and from this, our rights have been constrained ever since. Many of the systems put in place centuries ago, without significant change, have caused inequities that are still being felt today.”

— K.B., Vice President

“Equity. People behave differently when ‘skin is in the game’ vs. ‘being in the game because of your skin.’ Equal opportunity in basketball is this: everyone plays the same minutes. In regard to equity, coaches work with each player to strengthen areas of deficiency and proficiency. We’re equitable in how we treat and prepare the kids, but outcomes and playing time are usually determined by their efforts, not the coaches. The best players receive the bulk of the on-court minutes, unless your dad is the coach :)”

— S.B., Basketball Coach and Business Owner

“Equality. We aspire to be on the same level as white people, We get degrees and work just as hard as them, but they still look down on us because of the neighborhood we live in or the color of our skin.”

— A.B., Government Employee

“I want equity big bro. I’ve went years seeing blacks, for the most part, with no ownership. We are always shortchanged. They, white people, make their equity off of us. I have been in the real estate game for over a decade now. With the equity play, I can pass real assets down to my kids, which makes all the BS worth it. Thanks big bro for challenging me personally, financially, and socially.”

— D.M., Ex-OSU Football Player and Current Business Owner

“Definitely Equity. Financial resources in America are essential, the lifeblood and engine that make this country run. With regard to Equality, the system is dependent on inequity to function.”

— T.A., Vice President (Inner-City Public High School)

“We need both, but I lean more to the equality side. White men do not have to distinguish or choose between the two. What every citizen deserves, regardless of color, religious beliefs, or sexual orientation, is a fair and balanced shot at the American Dream. Provide me with both options; whether I fail or succeed, I was given a fair shot!”

— T.H., English Teacher (Inner-City Public High School)

You’re probably wondering, “What was your response Mr. Fundy?” Glad you asked. This might sound arrogant, and I certainly don’t feel this way now (thanks to an ample supply of the Lord’s humble pie). But for decades, starting at the age of nine, I never felt that whites were on my level intellectually. In my mind, I had no equals in the classroom. Thus, equality from an educational and even intrapersonal (or self-talk) point of view were never on my radar. In spite of being a black man with a built in away uniform. In spite of growing up in abject poverty and being told by neighborhood peers, in these exact words, “You ain’t never goin’ to be nothing but a poor kid from the ghetto.” In spite of being reared in a home without the other half of my paternal DNA present. The shackles of racial orthodoxy still exist, but I never allowed them to be placed around my ankles because of what’s in my mind and spirit. White slave owners knew back then what is intuitively still the case today: an educated black man or woman or child with an unshakeable resolve was (or is) an empowered soul. The body can be enslaved, but the mind is the key to freeing an embittered disposition. Equality is qualitatively subjective; it’s a heart issue. Equity on the other hand, is quantifiably objective. It can be measured by head and hunger initiatives.

Equality-equity discussions make some people incredibly nervous, depending on which side of the Robin Hood ledger account one falls. Taking from the rich to improve the prospects of the poor is how some critics read the situation. To a varying degree, their critique has validity. Sleight-of-hand tricks are unethical, regardless of an individual’s, family’s, or company’s balance sheet. Close friends of mine, affluent white families who are also staunch conservatives, have huge problems with the term equity outside of their well-insulated bubble. They assume it means equitable outcomes, or the implementation of a referee system to right the wrongs of historical transgressions (think slavery and Jim Crow) and widening net worth disparities (look these up by race; they’ll shock you!) Perhaps in the playbook of some social justice scorekeepers, but not in mine. Equity is elusive to the vulnerable, but exclusive to the venerated. Also known as the wealth accumulation stiff-arm of capitalism, this is what separates lane groups. It typically escapes the grasp of underdog lanes (aka the underclass), enlightens and frightens comfort zone lanes (aka the middle class), and extends the grip of inside lanes of privilege (aka the super upper class). I will expound upon classism in the last article of this series, mobility. Here’s a typical conversation I often have with “equity critics” from right-leaning, affluent backgrounds:

Me: In light of the protest movement and the George Floyd fallout, what are your thoughts on equity from a social justice point of view?

Equity Critic: It’s incredibly divisive and counterproductive in uniting people. Wouldn’t you agree?

Me: It can be, depending on how the narrative is spun. But why run from a term, equity, that you embrace on a daily basis? You have equity in your primary and secondary residences. You have equity in your investment accounts. You have equity in your multiple businesses. You have relational equity with your family members, most of whom, I’d imagine, are highly successful. You have equity with your extensive network of like-minded power brokers who, like you, can navigate every sphere of influence with relative ease.

Equity Critic: Well, I’ve never looked at it from that perspective before.

In closing, semantics matter a great deal when human dignity and earning a humanely dignified wage are on the line. Equity, as the “Brother in the Struggle” highlighted, is a legacy play. And every individual as a citizen of these United States should have the guarantor’s opportunity (but not the guaranteed outcome) to secure it. Life. Liberty. Pursuit of Happiness. Didn’t our founding fathers endow these attributes on all of us? For underdog lanes of color, what equity pathways can they pursue with your/my/our assistance? We must help them win the mental health game while wearing a permanent away uniform — black or brown skin — in color-coded America. We must offer to be their voice of comfort and civility in the face of injustice. We must help them develop mindsets and build skillsets for sustainable, employment purposes. We must help them lead when their leadership role models on the home-front, notably paternal seed bearers, are inconsistent or absent. We must help them amass legacy wealth, one opportunity brick at a time. Alongside my wife Monya, this is why we started our nonprofit organization and for-profit enterprises more than 20 years ago. To provide black and brown Americans with a comfortable and convenient seat at the equity table next to their white counterparts. Remember the sit-in (really sit-down) protest by four black college freshmen at a “white’s only” Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, on February 1, 1960? Stay tuned for the next article under the macroscope: justice. It, too, will likely be an uncomfortable and hopefully enjoyable read for you.

Related Articles

Nothing found.

MLK Installment #1

Lawrence Funderburke

The Power of Privilege: Are You Using Yours to Make Our World a Better Place or Bitter Space?

In decades past, privilege was synonymous with child-specific opportunities and responsibilities, as in certain siblings enjoyed more merit-based perks or benefits than their other brothers, sisters, or extended family members. Whether hanging out with friends, playing outside after school (now seen as punishment by so many of our kids!), or staying up late on the weekends, equality and equity were two separate concepts back in the household-privilege day. “Treat equally but trust equitably” was the de facto motto shared by parents and grandparents alike. “Treat” deals with fairness, while “trust” encompasses firmness. To be fair is just, but to be firm is a must, especially on the opportunity and responsibility side of the parental-child ledger account. Caregivers may not admit this, but we do have our favorites. (I don’t want to get anyone in trouble, just stating the obvious.)

Given our nation’s troubled history on race, the twenty-first century version of privilege has taken on a new meaning. But is this word solely and wholly now tied to skin color? Of course not! More on the far-reaching aspects of privilege later. In our weaponized, Americanized, and commoditized echo chamber, its connotative association is typically accessorized in racial garb. Weaponized in terms of how privilege is used as an “us vs. them” contrasting tool (better yet, a sledgehammer). It’s Americanized by virtue of the fact that when a US citizen visits multiple countries on different continents, he or she quickly realizes that privilege is usually connected to social class determinants rather than skin color diversions. It’s commoditized from the standpoint of a “one-size-fits-all” lens; individual benefits often mirror inherent group privileges, notably in the context of race. Herein lies our modernized conundrum on privilege: do embedded or endowed benefits of skin color cause, compound, or contribute to disprivilege?

Before weighing in, let me define disprivilege. It is the unfair hand, invisible in many instances, dealt to those who are “outsiders looking in” from a racial, societal, or organizational vantage point. And when you’re safely inside the privilege bubble, you’re often not aware of those stranded on the outskirts of it. Most non-Hispanic whites have (and in some cases, still do) enjoy the benefits of pigmented privilege on several fronts. They’re less likely to be profiled while walking in or around a store, driving through an upscale neighborhood, or being viewed as a potential menace to society. They’re less likely, and quite frankly less inclined, to have to “sell” their value proposition rather than to “prove” it. They’re more likely to benefit from “cultural fit” in corporate America, thanks in large (or in small) part to The Law of Familiarity. Buckle your seat belt; you’re about to go on an uncomfortable but necessary, growth-oriented ride.

I have dozens of examples, but this particular profiling story stands out. My wife Monya is a light-skinned African American woman, although some people assume she’s Hispanic or from the Middle East. Twenty years ago, our team, the Sacramento Kings, played on the road against the Los Angelos Lakers in the NBA Western Conference Finals. We stayed in the prestigious Beverly Wilshire hotel, steps away from Rodeo Drive. During my pre-game nap, Monya ventured into a high-end boutique and was immediately stereotyped as the proverbial “window shopper.” If you’ve ever been treated (or felt) like a second-class citizen in the presence of a sales person before — regardless of your racial makeup — it hurts. It’s often stigmatizing, demoralizing, and can even be traumatizing. No one paid attention to Monya until she walked by a commission-based sales associate and blurted out, “I want that, add that, and that.” No money should have to be spent to receive the debt of human dignity in order to grow humane capital.

I don’t know a black male over the age of 40 in my inner circle who hasn’t been profiled by law enforcement while driving through an upscale, predominately all-white community. Even when he lives there! Remnants still exist, but the double-takes and stare-downs seem to have subsided substantially, post-George Floyd. Back in college at Ohio State, I was roughed up and nearly shot by two white police officers. It was the classic case of mistaken identity, which was surprising given my high-profile status. Didn’t matter. They had a person-of-color (POC) narrative to uphold and a guilty-as-charged (GAC) suspect to apprehend. At the time, I stayed in a condominium on the periphery of Upper Arlington, a desirable suburb here in Central Ohio. Two blacks lived in this complex of more than 100 residents, me and my next door neighbor. Come to find out, he was a big-time drug dealer. Now, I grew up with “street entrepreneurs,” but I never associated with them. I didn’t speak to my next door neighbor, not once, for obvious reasons. I later learned that his vehicle and daily movements were being monitored by law enforcement. They pulled up in the parking lot on an overcast day in April of 1994, a few seconds after me and a good friend had just returned from a basketball workout. We saw the cops looking inside the window to my neighbor’s attached garage. Snitching is a no-no in the black community, so I didn’t feel inclined to share with the police any incriminating evidence about my neighbor, who wasn’t home at the time. Here is our conversation:

Me: Can I help you?

Police Officer #1: We’re just here to look around.

Me: Alright.

Police Officer #2: Where do you live?

Me: Right here. What’s up?

Police Officer #1: None of your business. (He walks over to my SUV and peers inside.)

Me: What are you doing?

Police Officer #1: (in a raised voice) Don’t worry about it. As a matter of fact, get on the ground!

Me: (Initially, I sat down instead of laying down on my chest.) Cool. Hey, my name is Lawrence …

Police Officer #2: (Guns drawn.) We don’t care who you are! Lay down on the ground! Right now!

My Friend: (crying) Lawrence, just do what they say.

Dozens of residents gathered around as the situation escalated. They saw me and my friend lying on the ground with our faces to the pavement. My girlfriend at the time, now my wife, was crying hysterically and imploring me to cooperate before things took a tragic turn. The officers, who I did forgive, finally admitted their error and apologized for the mishap. Their supervisor showed up about 20 minutes later. He was horrified; he instantly recognized me and apologized profusely. I didn’t sue the Columbus Police Department, and those two cops weren’t reprimanded for their actions. This was the classic case of guilt by association. Of course, I can recall more than 10 other unsettling experiences when “mistaken identity” reared its ugly head. Unfortunately, black disprivilege has been (and still is) a glaring problem in every sphere of American society.

In corporate America, the privilege bubble is deflating but it hasn’t quite burst. I’ve discussed this phenomenon with my mentor, Stephen Davis, former CEO of Bob Evans. He passed last year and I pledged to keep his mission alive. As a well-respected POC, he extended grace while holding others accountable for the chances, choices, and changes that needed to take place at the C-Suite level. In one conversation, he shared, “Black and brown executive prospects must often sell and then prove their value proposition before they’re taken seriously.” He added, “although we are praised for our ability to connect with others, a deficiency in ‘strategic thinking’ is what supposedly holds us back from professional advancement.” If you have an in-depth or even a cursory understanding of neuroscience, you’re keenly aware that the frontal lobe is where executive functioning takes place. Attributes such as planning, organizing, problem-solving, weighing consequences, and avoiding distractions are developed and fine-tuned in this region of the cerebral cortex. Coded terms can serve as disprivilege justifications. Strategic thinking deficits or contingency planning shortfalls are attributed to African Americans, language barriers or dialect challenges to Hispanic Americans, and a lack of relational equity or insufficient people development skills to Indian and Asian Americans by some organizations when reviewing C-Suite candidates. Affinity connections and affirming convictions serve as protective measures for the Law of Familiarity. To break out of the privilege bubble, we have to embrace people who don’t look, think, and act like our tribal affiliation. And no growth occurs without intentional discomfort!

In closing, I’ve highlighted the low-hanging fruit associated with racial privilege. However, there’s political privilege. C’mon now. We’re more friendly to neighbors, work colleagues, and even total strangers (at voting precincts while standing in line) who share our ideological viewpoints. There’s relational privilege. Thanks to oxytocin, sports fans of every color high-five each other in jam-packed arenas and stadiums when their team excels. Go Bengals! There’s financial privilege. Those who have more in life are often treated much better than those who have far less. Think about how we interact with someone in a three-piece suit needing directions compared to a homeless person asking for spare change. There’s educational privilege. Society places a premium on academic success and intelligence. When subject-verb disagreements occur in a conversation or are doled out on a noon talk show (aka The Jerry Springer Show), might we be inclined to look down upon that person who doesn’t quite measure up to our dialect standards? There’s nutritional privilege. Those of us who are fanatical about healthy eating and purposeful living might react in disdain, a scrunched nose or raised chin perhaps, when encountering someone who appears to value exercise and diet significantly less than we do. Now, how will you use privilege (or even disprivilege) to make our world a better place instead of a bitter space? Stay tuned for the second installment of this five-part series in memory of Dr. Martin Luther King’s bridge-building legacy.

Related Articles

Nothing found.

MLK Five-Part Series

Lawrence Funderburke

Why MLK’s Appeal to White Moderates Fell on Deaf Ears and How We’re Still Paying the Price Six Decades Later

If you think I’m calling out whites for all of the historical grievances experienced by people of color (POCs) in this country, you’re mistaken. But I am calling them, you, and myself up to the mountaintop of lasting change that Dr. King envisioned through his expansive and expensive faith lens in the valley of (in)decision. On August 28, 1963, MLK’s I Have A Dream Speech should have been viewed as the down payment for racial harmony in America. The audience was predominately black and brown, but whites were in attendance as well. The obligation behind (or in front of) MLK’s ominous and prophetic speech still applies today. And it is quite costly. You see, America is changing. Unfortunately, far too many of us confuse change happening around us as a sign and signal that transformation is occurring within us. This, my friends, is the classic case of delusion. Tough talk, I know. But let’s go and grow together on this change journey.

Why go back to a time — the contentious Civil Rights Era in the 1960’s — that many in our nation would soon forget? Well, America’s future is predicated by what we learn from our complicated past. No time for historical amnesia, but we do need to make ample room for experiential grace and personal accountability. Here’s what I mean. Grace is a tenet or prerequisite of the Christian faith. And for those of us over the age of 45, it was a ritualistic prayer or rote blessing we shared publicly or privately before each meal as children. Now, we can’t deal with the uncomfortable subject of race without grace. This doesn’t mean we forget, but rather, we choose to forgive and hold others accountable for the change that must take place personally, organizationally, and societally to bridge the racial gaps. Without accountability, frustration steps up. People may know how long they’re going to be given to change in order to implement a racial call up, but they won’t know what to do. And without grace, exhaustion creeps in. People may know what to do behind a racial call up, but they don’t know how long they’re going to be given to change.

As a college and former NBA player, I know this to be true: sports and life intersect on a number of fronts. In corporate settings, I make it a point to highlight this truth: “Too much defense and not enough offense usually results in an ‘L’ for a team.” The implication is clear. Whites, regardless of their political leanings, will back away from the change table, especially men in positions of power who are (or even feel) targeted. Blaming-shaming-framing tactics create distance rather than close it. The oxytocin window to trust-bond-love will be missed, an opportunity to connect with those who don’t look, think, or act like our tribal affiliation. In this video game era of sports, high-octane offense keeps fans, viewers, and sponsors on the edge of their seats. Thus, it’s incumbent upon me to provide a venue in which racial growth occurs through offensive tools rather than defensive traps. This encourages buy-in and empowers all vested parties when equity, justice, diversity, privilege, and mobility are discussed against the backdrop of race. I’ll feature each one of these five hot-button topics in coming days, free of guilt but full of conviction.

In closing, no change can take place without a recurring payment. Time out for racial equality IOUs. Now, if we celebrate the life of MLK, shouldn’t we honor his legacy also? He said a lot more than “I look for the day when people will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” Along with “I don’t see color,” MLK’s regurgitated saying is often quoted by many whites to provide racial cover. Allow me the liberty to share the essence of Dr. King’s appeal to white moderates while dissecting the prevailing theme embedded in his gut-wrenching jailhouse letters: “We serve the same God. We’re covered under the same blood of Jesus. However, we have very different skin tones.” They were shown a need, in graphic detail, but didn’t fulfill it. The result? A lot of innocent people were (and are still being) hurt in the process. Why? White moderates in the South and even North didn’t want to exhaust their racial, social, and political capital, so they backed away from the change table. Six decades later, here we are.

Let me leave you with something to ponder until my next post: