MLK Installment #3

The Justice of Just Us: What Does It Mean? Why Does It Matter? Who Stands to Benefit?

No justice, no peace. It’s a phrase we’re quite familiar with, given its racial, social, and political, pre-Covid overtones. Dr. King stated, “An injustice anywhere is an injustice everywhere.” Profound and provocative at the same time. When it comes to justice, black and brown Americans keep asking, “Why is it just us who feel this way?” Just us being scrutinized by law-and-order referees while sporting our permanent away uniforms. Just us being profiled or stereotyped while driving through upscale neighborhoods. Just us being seen as the proverbial window shoppers while walking around high-end department stores. Just us getting the short-end of the opportunity stick outside the workplace. Just us being passed up on a promotion inside the workplace as an over- or under-qualified job candidate, or finding ourselves as that lucky, “handpicked” actually, racial-quota charity hire. Bronze (Indian) and beige (Asian) Americans are also raising their voice of concern. On the higher-ed admission front, they’re asking, “Why is it just us, or our kids, who are unfairly being punished by top-tier colleges and universities because we overrepresent the minority-student population?” And blanco Americans in rural areas — the invisible white class — have equally, if not worse, life outcomes as inner-city communities of color. Their voice needs to be heard and respected just the same. A justice-just us framework will be explored in this third installment of the MLK series. Buckle up; it’s time to go on another bumpy ride.

A Rogue Teacher on a Seek and Destroy Mission

I don’t like living in the past. But for illustrative purposes, sometimes it’s necessary to go back (but not stay) there to explain how we arrived here. The year was 1981, not 1881. I was a fifth-grader at Westgate Elementary School. Across the country, inner-city blacks in the 1970s were bused to better performing schools in predominately white neighborhoods. Institutional racism is one thing, but educational injustice is a whole ’nother ball game. We, Americans in general, can have a civil debate about what fundamental rights we’re owed and who should pay for them. However, every child — regardless of race, gender, or economics — deserves a quality education.

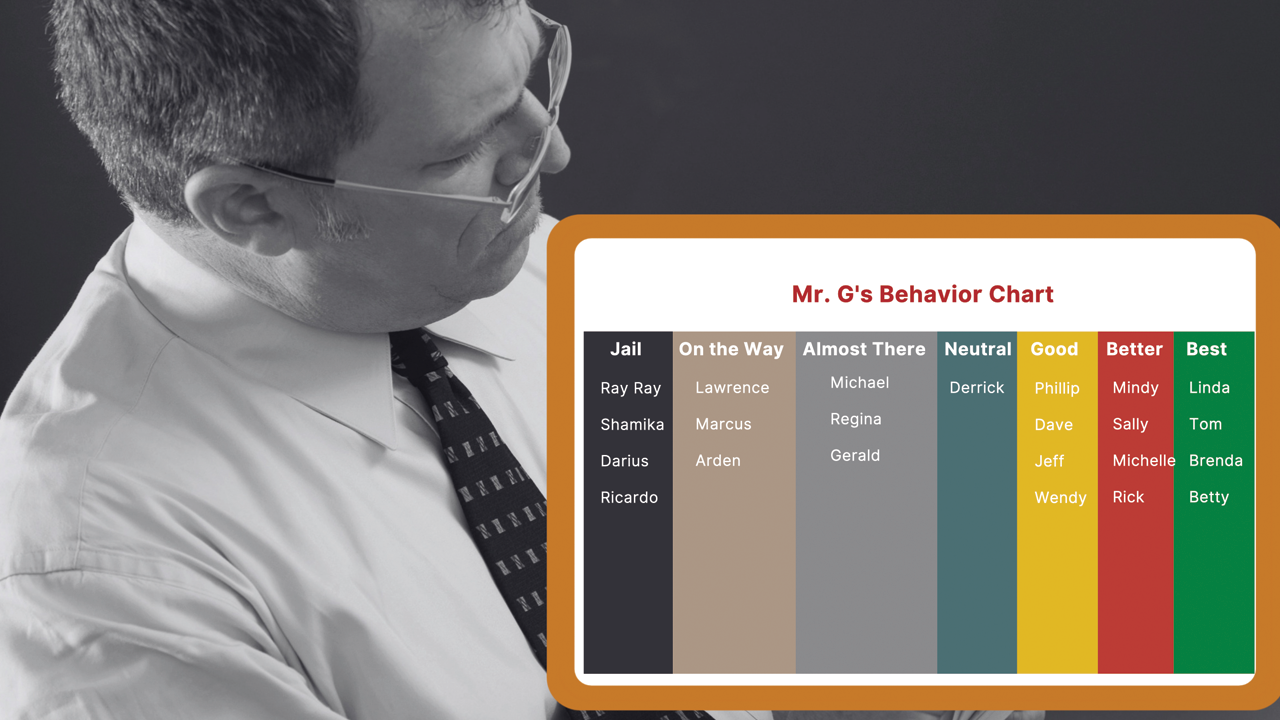

I, along with several classmates, were victims of academic bigotry over the course of an entire school year. Mr. G, one of my elementary school teachers, was an outlier. In no way did his unconscionable deeds cast a dark cloud over the wonderful experiences I had overall in the classroom as a kid being taught primarily by white teachers. The color of their skin didn’t matter to me but their commitment to my educational development did. Ready for this? Mr. G had a color-coded chart in his classroom that rewarded or punished behavior based on his jaded worldview. He served as a judge, juror, and probation officer, whether or not the sentence fit the crime. Looking back, I don’t know how he was able to get away with his demented experiment. Three decades later, I was told by a colleague who worked at the school with Mr. G that he taught with a racial bias. Duh, thanks for the heads up now.

Mr. G would advance a student to the right side of his chart — “good,” “better,” or “best” — for appropriate behaviors. These were the upstream, free-flowing conduct blocks. Questionable behaviors were demoted to the left side of his chart, the downstream blocks, including “on the way,” “almost there,” and for many of the black students in class, “jail.” Think about the seeds Mr. G was trying to plant in our minds: intellectual inferiority, criminal susceptibility, and educational incapability. Latitude was given to the white students for minor offenses such as talking in class, chewing gum, or horseplay, but very rarely did he extend any grace to black students. His methods emitted a foul odor of unfairness. And he wore this putrid cologne every day to annoy us even more. His merit-based behavior system, which he took great pride in, allowed some students to enjoy extra perks — treats that he brought to school or a special recess granted to “worthy scholars” at the end of the school day.

Mr. G’s Behavioral Chart

Mr. G didn’t particularly like me: I didn’t fit his sick narrative. Poor black boys from broken homes are supposed to be academic casualties, incapable of adding anything substantive to the educational experience. I could go on and on about the misdeeds of Mr. G — making us stand in the corner of the room with our hands up and feet spread apart as though we were being (or one day would be) arrested, placing our desk out of view behind the coat wall, or slapping our hands with a plastic ruler — a man who was in his mid-to-late 50s nearing retirement back in the early 1980s, which meant he would have likely come of age during the racially divisive era of the 1950s and 1960s. He was Archie Bunker, of All in the Family fame, masquerading as an educator. To imply that our path in life would inevitably lead to prison (in all its forms) is mind-boggling for someone who presumably took an oath each year to educate all children — black, brown, or white — in Yankee territory.

I am not sure Mr. G is still alive, but I don’t hold any animus toward him or his offspring (since the apple doesn’t usually fall too far from the tree). Extended mercy is for my benefit, not his. No easy task when you were intentionally and systematically abused. But you know what’s even more sad about the story. White teachers and school administrators didn’t intervene on our behalf. They were aware of Mr. G’s methods and disdain for the black students who had invaded “his white, middle-class comfort zone” on the hilltop. They allowed Mr. G’s racist attitudes and sinister actions to create a toxic learning environment with legacy implications. For this reason, they were equally guilty. Affecting and infecting the fragile minds of poor black kids who were (and still are being) written off as hopeless misfits is abominable. Even today, many stand by and do nothing about academic gaps, wealth inequalities, mentoring shortfalls, incarceration disparities, economic vultures, and food deserts (or the lack of healthy food choices) that are glaringly obvious in distressed, urban communities. Failing those Americans who need every ounce of positive momentum they can secure to have a legitimate shot at life is un-American. What can you do at a grassroots level to be a solution and not an accessory to these inhumane crimes?

“How Many Strokes Are You Giving Me?”

I enjoy playing golf. The camaraderie with other golfers. The beautiful landscape. The clarity and creativity of thought, which immaculate greens tend to generate, and according to color theory, may explain why so many business ideas, partnership mergers, and handshake deals take place on the golf course. It’s a game that I’ve attempted to play for over 20 years, thanks in large part to Tiger Woods. His ascendency in the late 1990s and early 2000s as the world’s best golfer inspired many people of color (POCs) to try their hand at a sport that was historically viewed as “the domain of privileged white men.” Speaking of hand, my handicap is an impressive 25. Don’t laugh. My athletic skills are such that I will hit my fair share of Tiger Woods shots. But as a golf hack, my Tiger Whoa Whoa shots keep me humble when they venture off the fairway, deep into the woods. And yes, given my impoverished upbringing, I’ll risk catching poison ivy to retrieve lost golf balls, even with two dozen of them in my bag. Now, I’ve had plenty of expensive and time-intensive lessons through the years from great coaches, but for some reason, my handicap hasn’t budged much. Perhaps I need to spend more time practicing and playing to master a consistent golf swing. Then again, so much can go wrong trying to hit a tiny ball using custom-made clubs with extensions to accommodate my 6’9” frame. (I recount this story in greater detail in the book, Sociopsychonomics: How Social Classes Think, Act, and Behave Financially in the Twenty-First Century.)

If you’re not familiar with this sport, a golf handicap allows amateur golfers — on any course — to compete against higher-skilled players. Golfers with a ‘high’ handicap, like me, are allowed a higher number of extra strokes over the course par. Those with a ‘low’ handicap tend to take fewer strokes to navigate the course (reference: fairwayapproach.com). In golf, a player’s handicap is a measurement tool to gauge skill level but not necessarily heart or intestinal fortitude. As a lifelong competitor, I’ll take the golf strokes and make the most of the opportunity, no matter who or what weather conditions I’m playing against on a particular day. The law of favorable averages (LOFA), or strokes of good fortune, eventually bend in the direction of those who have been shortchanged in life. That is, if they’re resolute in achieving better life prospects, legacy pathways, and leadership paradigms. They just need a few breaks for their opportunity ball to role in the equity cup.

Golfing aficionados engage, often unaware, in affirmative action practices every time they participate in the sport. Although not a perfect tool, a golf handicap bridges the gap between higher-skilled and lower-skilled players. And for some avid golfers with decent handicaps who are invited to play on a prestigious golf course at an exclusive country club by the host, a scratch golfer by the way, they’re quick to ask as tee time approaches, “How many strokes are you giving me today?” With affirmative action practices in higher education, “strokes” or special preferences are given to some incoming students who aren’t white affluent nor do they qualify as minority adjacent, or young people from Indian- or Asian-American backgrounds with impressive academic scores. Whatever caused or contributed to the academic gaps experienced by vulnerable POC students at the front end — a toxic environment, poor role modeling, negative peer influences, economic challenges, and/or revolving setbacks — let’s find a way to close them at the back end with a quality education, relatable tutors, career mentors, a meaningful degree, and beneficial networking contacts secured in a higher-ed (or trade school) setting. Admission quotas are fraught with perils, but at least they give those on the fringes of society a firmer chance to move up a social class or run in a better opportunity lane.

The Collaboration Arena: A Judgment-Free Zone for Change

Allyship was the word of the year in 2021, this according to Dictionary.com. It’s actually an old school word for a new school world. Simply put, it’s sticking your neck on the line for others outside of your affinity group, kindred connection, or tribal affiliation. White abolitionists who were instrumental players in The Underground Railroad movement risked their lives and livelihood for black slaves. Allyship is about honor, not duty, understanding, not guilt. Allies find ways to right the wrongs of injustice without pointing fingers — the blaming, framing, and shaming contest. When you point a finger at someone, some thing, or some system where disprivilege or inequity occurs, guess what, you have three pointing right back at you. And if you’re down with The Three Times Rule, then you are keenly aware that a change agent must transform into something better before creating changeable pathways for someone else. Got it? The Collaboration Arena practices holistic allyship, really an accountability partnership rooted in goodwill, for white men who hold positions of power, privilege, and prominence.

On January 28, 2021, I hosted a dinner for 20 white men at the C-suite level. On my own dime and time, while also being cognizant of Covid protocols, I invited them to a three-course meal at Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse. Now, defense is great for sports team. However, offense is how you keep players excited about the prospects of winning. And yes, white men in positions of influence will be instrumental in the outcome of the racial connectivity game. Only two blacks were in the room, me and the moderator, Steven Davis, the former CEO of Bob Evans restaurants. I spoke passionately and persuasively for about 10 minutes at the onset — using the language of sports analogies as the backdrop — to set the tone for the evening. I opened with these comments, “Gentlemen, you don’t have to sit down, but you do need to scoot over. It’ll be tight, but there’s enough room in the opportunity front seat for those who don’t look, think, and act like you.” I added, “This is our locker room moment. Let’s talk about the game that you have the power to influence as opportunity coaches.” That evening we had some candid conversations on what needs to change in corporate settings and inner-city communities. No one got a free pass. How did we pull this off? Simple. We created an environment where an emotional safety net was present before they even arrived at Ruth’s Chris. Had this not been the case, they would have declined the offer. Straight, conservative white men in C-suite positions have a target on their backs. They’re at the bottom of the proverbial football pile; they now know what it’s like to struggle breathing, figuratively speaking that is. Instead of pilling on, I am pulling off. Working with them through reasonable measures as opposed to working against them constrained by unreasonable metrics was (and still is) the key to helping companies hire qualified POCs through dignified gestures. Diversity for the sake of diversity is a bad thing because it’s based on a zero-sums game: whites regrettably lose and people of color inevitably win. But diversity that appreciates the richness of other cultures, classes, and communities creates a dynamic and panoramic ecosystem where everyone has the right but not the guarantee to flourish.

Let’s close on a positive note. I was invited to a political gathering several years ago (and haven’t been invited back since) to discuss wealth disparities in the black community. Famous dignitaries, CEOs, political figures, celebrities, and other former pro athletes were in attendance. Panelists were given six minutes to share a message that resonated with the audience, most of whom were POCs. My mic drop moment came when I shared this timeless truth at the onset to free black folk, financially or otherwise, from the shackles of America-induced trauma: “We can’t hold whites hostage for all of the historical injustices that have been perpetrated against our people. We must let them go for the sake of our legacy, not theirs.” Roughly half of the attendees agreed with my advice in principle, and the other half rejected it in practice. Forgiveness doesn’t mean blacks must forget about slavery, anti-literacy laws, lynchings (almost 6,000 documented cases), Jim Crow, segregation, housing discrimination, and other ancestral wounds too numerous to mention. No, but we do need to forgive while holding white America and ourselves accountable for the change that should take place. This ongoing choice — a settled decision without a cutoff switch or expiration date — rests in our hands. Choosing to forgive can’t be a head or heart matter; it’s not always going to make sense or feel right. But it must be a hunger initiative to feed and nourish the human spirit. And this, my friends, can’t occur without the accompanying payment of grace, a formidable ally that can pay dividends for generations to come.

GRACE + ACCOUNTABILITY = RACIAL CONNECTIVITY

This simple formula isn’t easy, but it is absolutely necessary to move our country forward. Diversity, in the form of cultural capital, is next up in the MLK series.